Bhutan Festival Tour, and What it Taught Me About Time and Belief

Bhutan Festival Tour, and What it Taught Me About Time and Belief

I came to Bhutan under the pretext of attending a festival. That is how travel is often justified. It’s a reason we can point to when asked why there, why now. But the truth is, festivals are only partly about the dances or the costumes. A Bhutan festival tour offers something more subtle: a structure, a scaffolding, into which a community fits its memories. What one witnesses is certainly a spectacle, but also a kind of rehearsal of belief.

The monks arrived in masks of such grotesque charm that, in another place, they would have been photographed for postcards and reduced to curiosities. Here, though, they carried weight. They stamped the earth for the continuity of something that does not need an audience. I thought then how foreign it is to us, in the West, where meaning must be announced, explained, justified. In the quiet of a Bhutan festival tour, the meaning was simply assumed, and that was enough.

I had come to Bumthang to attend Jambay Lhakhang Drupchen, and there, in the temple courtyard, I found myself both inside and outside the order of the day. Inside, because hospitality draws you in whether you deserve it or not. Outside, because there is a limit to what you can ever understand when the gestures belong to centuries that are not yours. And yet, in that gap, something valuable is learned, if not knowledge, then at least the discipline of watching without intrusion.

The first time I laid eyes on Jambay Lhakhang, I felt as though I had stumbled into a place outside the ordinary measures of time. Lhakhang means temple, a dwelling for sacred images and daily worship, unlike a monastery, which is occupied by monks and shaped by the routines of communal life. The building is small, intimate, its walls faded but steadfast, as though it has absorbed centuries of devotion in silence. Watching the villagers arrive, carrying offerings, lighting butter lamps, bowing with the ease of habit rather than ceremony, I understood that the Lhakhang is a living centre of faith, personal, immediate, and utterly present, unlike a monastery, which asserts its authority through discipline and hierarchy. There was a quiet astonishment in me: how something so modest could hold such gravity, how devotion could feel both ordinary and profound in the same moment.

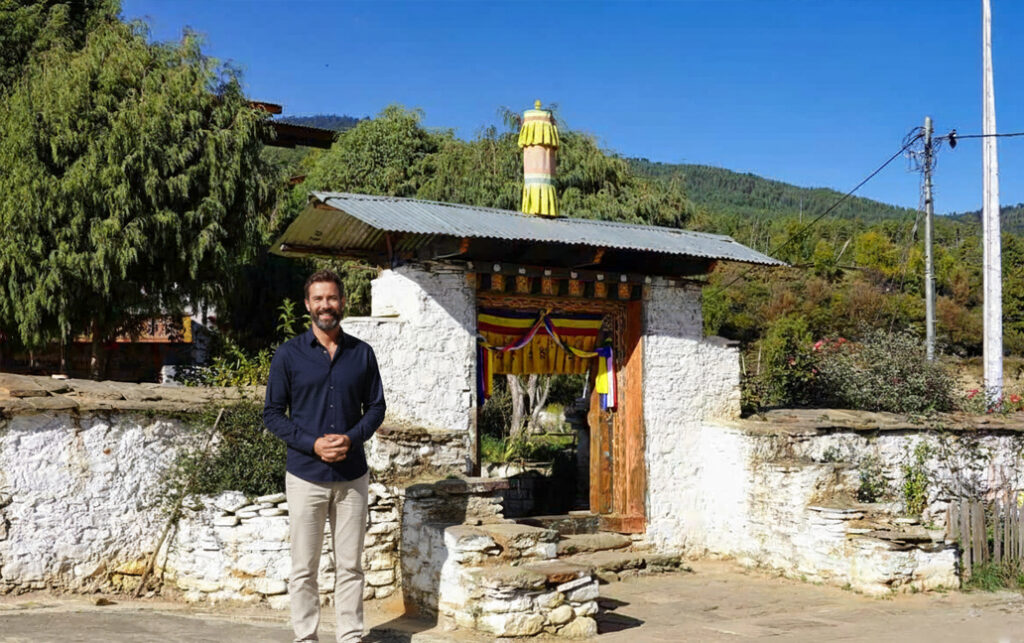

The journey to Bumthang was its own small education in patience and scenery. We traveled from Paro to Thimphu, where the capital’s bustle seemed to tiptoe between modernity and tradition, before winding through the misty Pobjikha Valley, a place so fertile and quiet it felt almost conspiratorial in its perfection. Our guide, Sonam, kept us moving with a gentle authority, his humour slipping through in small, perfectly timed remarks, like reminding me that my umbrella, though heroic, was hopeless against Bhutanese drizzle. He knew when to talk, when to let the mountains speak, and when to nudge me toward yet another bend in the road that revealed a view so impossibly beautiful it made me suspect the country had a sense of irony. By the time we arrived in Bumthang, after a 5-hour drive, I felt both worn and exalted, a traveller in possession of too many impressions to untangle, yet willing to let them settle where they would.

Jambay Lhakhang Drupchen – Bhutan Festival Tour

I arrived at Jambay Lhakhang under the weight of expectation, though I had long since learned that anticipation rarely survives the first encounter. The temple itself, perched quietly in Bumthang Valley, is modest in scale but dense with history. Its walls, faded and unassuming, bear witness to centuries of devotion, and the moment I stepped inside the courtyard, the past seemed to settle around me like dust disturbed by careful hands. The festival had already begun in the evening with the burning of the sacred fire, Jinsi, whose smoke rose into the chill air with a patient authority. Watching the Black Hat Dance, I was struck not by its colour or motion, but by the way it claimed the ground, stamping out the invisible weight of malevolence as naturally as one might sweep the floor.

The Dance of Offering followed, less spectacle than transaction, a ritual in which the bodies of evil spirits were ceremonially surrendered to deities. Outside, the Fire Dance demanded an audacious courage: villagers passed through the burning arch of pine, the flames licking at the edges of ordinary life, a purifying act that seemed to take nothing for granted. By nightfall, the courtyard was thick with smoke and the flickering light of butter lamps, illuminating faces that bore no surprise, no performance, only quiet recognition that this is how the world is ordered here.

The next day, the festival revealed itself in its fuller breadth. Dorling Nga Cham, the Dance with Drums, and Dorling Dri Cham, the Dance with Swords, moved through the morning with a sense of inevitability. Each beat, each gesture, carried blessing and meaning as if the dancers themselves had become conduits of devotion. The Dance of the Rakshas and the Judgement of the Dead, dramatizing the passage after death, held a curious gravity; it was neither theatrical nor sensational, but exact, precise, and complete in its enactment. And when night returned, the midnight Naked Dance, sixteen men performing ancient tantric rituals, reminded me that ritual here is unembarrassed, a force entirely unconcerned with the observer’s sensibilities.

There were other dances too, smaller, eccentric, seemingly incongruous, the clown dances, the drum-beat dances, and Tercham, the Dance of Treasure Revelations, all threaded together by a single, unspoken insistence. Each act was a lesson, each gesture a declaration that faith endures not by proclamation but by repetition, by integration into the daily life of a community. Watching it all, I understood that the festival is not for outsiders, yet its presence is unavoidable, like the steady pulse of the valley itself. One learns less about performance and more about the quiet insistence of a people who have learned to fold devotion into every movement, every breath, every passing year.

I left Jambay Lhakhang with a quiet astonishment that did not fade with distance. The festival had impressed itself upon me not as a spectacle, but as a demonstration of continuity and patience. I felt the weight of centuries pressing gently against the present, a reminder that devotion, when practiced without expectation or performance, has a gravity that lingers in the bones. The valley, the smoke, the laughter of children, and the measured movements of the monks remained with me, lodged somewhere between memory and sensation, refusing to be simplified or neatly explained.

Afterwards, there was a stillness I could not quite name, an internal space shaped by witnessing something enduring and unselfconscious. I noticed the pace and pretense of my own life in comparison, and it seemed absurdly loud. On this Bhutan festival tour, I had learned that faith and tradition do not need dramatics; they are stitched into daily existence, observed rather than proclaimed. And in that realization, I felt both humbled and fortunate, carrying with me a fragment of that quiet steadiness into the ordinary days that followed.